Priorities

PIFC lobbies all branches of California state government and organizes political and grassroots advocacy. The insurance industry is an important part of California’s economy and serves diverse communities in every corner of the state.

Issues of Importance to PIFC

California’s rules for establishing home and auto insurance rates are uniquely complicated compared to the regulatory framework in other states and countries. As a result, California consumers pay some of the highest costs for insurance in the country.

Advocating for a fair system to calculate adequate insurance rates is one of the most important issues to PIFC. Without a reasonable and predictable rate making process, California consumers have fewer choices than are available in other states, with much less ability to find the products, services, premium, and coverage that best suits their individual and family needs.

California’s insurance rating law has not been updated since Proposition 103 passed over thirty years ago. Despite dramatic advancements in the auto industry, computer technology, and analytics.

While the auto industry and insurance industry have changed with the times, Proposition 103 has not. The complicated rules implementing Proposition 103 over the past thirty years have become antiquated, anti-competitive and need modernization.

PIFC has identified the following issues as opportunities for modernization:

Homeowners Insurance

Proposition 103

Proposition 103, which passed in 1988, required insurance companies to roll back prices by 20% and mandated that future rates be approved by the California Department of Insurance (CDI). Through this ballot initiative, the Insurance Commissioner became an elected official. Proposition 103 also required prior approvals of property and casualty rates, including homeowner insurance. CDI enforces the insurance laws of California and has authority over how insurers and licensees conduct business in California.

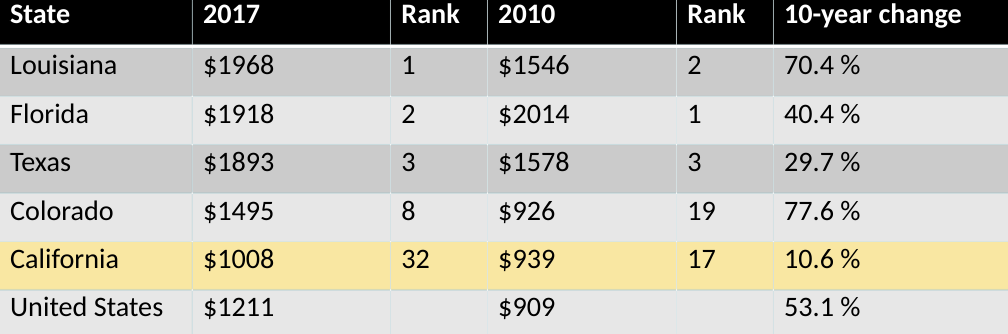

After Proposition 103, insurance rate increases, and decreases were approved by the elected Insurance Commissioner. This has created rate disparities between California and the rest of the United States. Average California premiums have not kept up with the rate of inflation and rates have been kept artificially low compared to other states. These statistics are especially startling when compared to other states experiencing high levels of natural disasters, like Louisiana and Colorado. As seen in the chart below, between 2010 and 2017, California’s average insurance premiums increased by only 10.6%. The average across the U.S. was a 53.1% increase. Colorado, a state with similar historic losses in wildfires, saw its insurance premiums increase by 77.6%.

Source: National Association of Insurance Commissioners

Acknowledging Wildfire Risk in Homeowners Insurance Rates

Extreme fire risk near people and property is growing. This risk has been exacerbated by longstanding fire over-suppression, which allowed excess fuel growth and unnaturally high tree density. This has made trees more vulnerable to insect infestation following California’s lengthy drought, resulting in a massive tree die-off of at least 163 million trees. While this process has unfolded, development into high-risk areas has continued unabated. Many of these risk factors have evolved slowly over decades, but it is only recently that the true magnitude of the fire-threat became apparent with historic wildfire damage and losses in 2017 and 2018, as well as the fires in 2020.

The ongoing impacts of climate change on California’s wildlands continue to create critically dry fuel conditions and longer, more severe fire seasons. The state experienced 4 of the largest 20 wildfires in its history in 2021. California homeowners’ insurers have experienced major insured losses over the past several years. The 2017-2018 California wildfire season was the most devastating in terms of loss of life, and insured losses of $26 billion dollars, according to data from CDI. Under existing CDI rules, insurance premiums are largely determined by past losses and loss related expenses. These historic financial losses place tremendous upward pressure on the price of homeowners insurance, and have forced many insurers to safeguard their solvency by limiting the amount of insurance they sell in high fire-threat areas of the state.

In 2020, PIFC supported legislation, AB 2167 (Daly) and SB 292 (Rubio), that would create a comprehensive framework to increase the availability of admitted market insurance in high fire-threat areas and help reduce risk and loss through individual home hardening and community-wide wildfire mitigation. Although the legislation was eventually halted in the legislature, PIFC continues to work on solutions to increase the availability of home insurance in California.

FAIR Plan Insurance

The California Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) Plan was established to meet the needs of California homeowners unable to find insurance in the traditional marketplace. The FAIR Plan is not a state agency, nor is it a public entity. There is no public or taxpayer funding.

The California FAIR Plan guarantees all property owners access to fire insurance.

All admitted homeowner’s insurance companies are required to be members of the FAIR Plan as a condition of doing business in California. The FAIR Plan operates without any state financial support. If the FAIR Plan is short of funds, it will assess admitted insurers, as required. The FAIR Plan does not cover water damage, liability, or theft. These coverages can be found in policies known as Difference in Conditions, or DIC, and can be added by homeowners as a wraparound policy.

The FAIR plan has historically insured approximately 123,000 policies. However, the number of homeowners in the FAIR Plan is rising in high fire risk areas, reaching 241,000 polices as of December 2021. This growth signals a problem in the regular, admitted market. For residents unable to find an admitted market policy, most likely those in the wildland urban interface (WUI), they will pay much higher premiums if forced to obtain coverage through the FAIR Plan. Allowing the FAIR Plan, “the expensive market of last resort”, to grow too large can threaten the sustainability of the California admitted insurance market. The admitted insurance market faces the risk of a market share-based capital call if the FAIR Plan’s surplus and reinsurance are insufficient to pay claims after a major catastrophic event.

Insurance “Rates” versus “Premiums”

There is a difference between insurance “rates” and the “premium” a particular homeowner pays to their insurer. The rate refers to the average price paid by customers that will generate an adequate amount of money required to cover the insurer’s anticipated expenses and make a reasonable rate of return. The “premium” that any particular homeowner pays is the result of the approved rating plan, or class plan that uses a series of positive and negative factors to determine the actual price paid. The class plan spreads the cost required to cover the insurer’s losses, expenses and returns, as defined by CDI regulations, among the insurer’s policyholders based on a set of factors also approved by CDI. A factor that reduces the premium charged in one area must be offset by a factor that increases the premium charged in another area. When those factors result in an insurer charging premiums inadequate to pay for losses associated with a category of homes, the gap must be filled by higher premiums charged for categories of homes with lower losses.

Insurance subsidizes those with losses through the premiums paid by people without losses. Considering subsidies in a larger sense, determining how risk will be priced and how groups of insureds will be assembled to share the risk will create financial incentives and disincentives. Premiums that were historically paid by homeowners in the WUI were substantially subsidized by lower risk policyholders in urban areas. Actions to reduce this subsidy will cause WUI premiums to rise independently of any consideration of the new normal in wildfire danger, and the billions of dollars in recent losses throughout California. For example, effective April 1, 2019, FAIR Plan policies with the lowest risk of wildfire had a rate decrease of between 10-30%, while policies with the highest wildfire risk received as much as a 69% increase according to CDI.

The ability for insurance companies to appropriately distribute and diversify risk in the policies they write is vital. Insurance modeling is done with the assumption that one or two homes may burn, not entire communities as has occurred the last two fire seasons. The importance of policy diversity is seen through Merced Property and Casualty, an insurance company that was bankrupted by insurance claims from the Camp Fire. The small San Joaquin Valley insurance company had assets of approximately $23 million, but the insurer anticipated claims from Paradise properties to be as much as $64 million. The company was founded in 1906, and sold insurance throughout California, while the company wrote plans throughout Central California. The concentration of policies in Paradise is what caused the company to become insolvent.

PIFC supports public policy changes that empower insurers to get sustainable rates that allow them to serve high fire risk areas without jeopardizing their solvency. Insurers must also be able to analyze their overall portfolio to ensure they are not overly concentrated in any one area exposing their underwriting to undue risks.

Proposition 103 & Auto Insurance

Intervenor Reform

Nearly 30 years ago, consumer activist Harvey Rosenfield wrote and helped qualify Proposition 103, the November 1988 ballot measure that overhauled state regulation auto insurance rates. The initiative, dubbed by supporters as the “Voter Revolt to Cut Insurance Rates,” also contained a provision that got little attention during one of the most expensive campaigns in state history: outsiders could challenge proposed insurance rates and get reimbursed for their costs.

As reported by the Sacramento Bee, “The so-called intervenor process has become a significant source of revenue for the nonprofit founded by Rosenfield and its successor, Consumer Watchdog. More than three-quarters of the $17.6 million in intervenor fees awarded since 2003 have gone to Consumer Watchdog or its predecessor, state records show. California is the only state that allows outside groups to participate in the home and auto insurance filing process. Yet there is still far from consensus on what the process has saved state residents, if anything.”

California has the seventh most expensive auto insurance market in the United States according to Forbes, partially due to the intervenor process. PIFC supports the concept of transparency and public participation in rate approval but does not support how the intervenor process currently operates.

With nearly 1,400 employees, the CDI is the largest consumer protection agency in the state. CDI has increased staff and expertise since the implementation of Proposition 103 over thirty years ago, and its staff conducts reviews of all rate requests. The intervenors simply duplicate work already performed by CDI, and do not have to demonstrate that they bring any new information to the table beyond what CDI is already considering.

Intervenors have made millions of dollars from this system. These fees are paid by insurance companies through the policyholder funds of consumers purchasing auto insurance in California. The 2015 analysis from the R Street Policy Group published average days for rate filing resolution from six states. California took an average of 138 days to resolve these rate filings, but if an intervenor got involved it increased to 343 days. New York had the next highest average rate resolution of 57 days.

Consumers, insurance companies, and CDI all benefit from a quick and efficient rate approval process, but intervenors benefit when the approval process is drawn out, as they are able to bill more hours. Intervenor expenses are paid by insurance companies but the true cost is born by California auto insurance customers.

PIFC believes public participation that aids CDI decision making is a benefit to the public and insurance companies, but the current intervenor system does not accomplish that.

PIFC supports a legal change that would require intervenors demonstrate consumers would be harmed without their involvement, and they would need to provide non-duplicative value to what CDI staff is already doing before being granted the right to profit from an insurance rate review.

Preserving Optional Rating Factors: Affinity Groups

Auto insurance provides liability, property, and medical coverage in the unfortunate event of a crash. The main factors that decide how much a driver pays for insurance are:

- The number of years driving

- Annual mileage driven

- Driving safety record

Proposition 103 also permits insurance companies to use optional rating factors, approved by the Insurance Commissioner, like completion of driver training, type of use, and academic standing. Additionally, Proposition 103 explicitly allows insurers to issue coverage on a “group plan”, without restriction as to the purpose of the group, occupation, or type of group. These discounts are known as affinity group discounts. Some examples may be a discount for an alumni association or for nurses. These discounts are subject to rigorous requirements. Each discount is filed publicly, supported by data and subject to CDI review and approval.

Yet, in recent years, CDI has taken action to limit the usage of optional rating factors and affinity groups. In 2019, CDI halted the use of gender as a rating factor, eliminating a discount for teenage girls of about 6 percent on their premiums.

Currently, CDI is proposing regulations to restrict the use of affinity groups. According to CDI, 6.8 million Californians receive an affinity group discount. Millions of consumers from all walks of life utilize group auto insurance discounts including nurses, teachers, firefighters, police officers, librarians, recent college graduates and small business owners to name a few. In fact, 73% of affinity group discounts are received by drivers making less than $50,000 per year. Eliminating affinity group pricing will cause low-income Californians to lose their discount and face higher insurance rates.

Additionally, changes to optional rating factors require the insurance industry to spend tens of millions of dollars to implement systems solely for the purpose of further restricting available discounts.

Enhancing Product Offerings: Telematics

Proposition 103 gave sweeping authority to the elected position of Insurance Commissioner to approve and regulate innovation in the insurance market. Due to various political factors, this has led to the unfortunate result that innovation is routinely discouraged and stymied. Many people are familiar with the disclaimer at the end of insurance advertisements on television: “Not Available in All States”. This disclaimer generally means that an insurance product is available everywhere but California. Examples of discounts not available in California include: accident forgiveness, new car replacement, paperless discounts, electronic funds transfer (EFT) discounts, and discounts based on driving behavior.

One specific technology that PIFC strongly believes would build awareness of the connection between driving behavior and insurance rates is telematics. Telematics technology is a powerful tool that gives drivers the opportunity to use their actual driving behavior as a factor in what they pay for auto insurance. Unfortunately, Californians currently cannot access this technology which 49 other states allow. Using data accessed through a driver’s smart phone or ports located in vehicles, telematics can measure behavior, such as:

- Braking – Harsh or abrupt braking

- Acceleration – How quickly the vehicle accelerates

- Speeding – Based on a variable speed in excess of the speed limit and by road type

- Distraction – Phone position (held or fixed) and screen interaction

Drivers often only vaguely understand the link between their safety record and how their insurance is priced. Unless their price goes up significantly after an accident or speeding ticket, consumers do not always link price to the way they drive. Telematics technology provides real-time feedback that can help change bad habits and encourage good ones.

CDI currently chooses to ban such discounts. Under CDI rules, insurers can get permission to use discounts if the Insurance Commissioner agrees that the rating factor is substantially related to the risk of loss. Insurers can demonstrate this relationship using actuarial science. But CDI, as a matter of policy, continues to reject insurer requests to bring more discounts to the insurance market.

Thus, insurers are left with denials of new products and discounts, yet California is a leader in innovation and technological sophistication in most other industries. Instead, consumers are stuck with an antiquated regulatory system in which innovation and progress is dramatically stifled by a changeable framework.

PIFC supports a legal change to create predictable, fair rates that will increase insurer competition and deliver benefits to California consumers.

PIFC supports allowing insurance companies to retain and expand product offerings if they can demonstrate it is related to a risk of loss.

Insurance Business Challenges

Abusive Litigation Practices – Policy Limit Demands

Consumers buy liability insurance to cover expenses they may incur if they cause an accident. When an insurance claim is filed against an insurance company’s customer, the insurance company has a legal duty to settle. The duty to settle requires the insurance company to accept a reasonable settlement offer that is within the limits of liability of their insurance customer’s policy.

If the victim of an accident believes they have not received just compensation, they, or more likely their legal representation, can send a policy limit demand to an insurance company. A policy limit demand will demand the monetary value of the policy limits of an insurance policy. An insurance company that unreasonably rejects a policy limits demand by placing its own interests above those of their insurance customer may be liable for bad faith and subject to liability more than the policy limits.

Policy limit demands are challenging for insurance company claims professionals because a demand compels them to make important decisions regarding payment of policy limits when substantial uncertainty exists regarding the claim.

Plaintiff lawyers take advantage of the opportunity to show an insurer was acting in bad faith and receive more compensation. This can cause some plaintiff lawyers to submit convoluted or purposely vague and ambiguous time-limited policy limit demands, with the intent of orchestrating a “denial” of the demand through a failure of acceptance. Examples of this unscrupulous gamesmanship include demands:

- Made with less than 5 business days to respond

- Specifying that any counter-communication will be deemed a rejection of offer including requests for clarifying information

- Sent to inappropriate addresses at insurance companies which cause delay in processing

- For medical or wage reimbursement higher than previously documented with no reports or records of substantiating alleged injuries or time lost at work

- Requiring a signed affidavit from CEOs at multi-national companies

Insurance carriers need time to adequately investigate claims. Pressure tactics in policy limit demands do not benefit consumers. Quite contrarily, they drive up claim’s costs leading to higher insurance premiums.

PIFC supports public policy to create a balanced and consistent legal system by placing reasonable parameters around insurance policy limit settlement demands.

Duplicative Privacy Regulations

For nearly 40 years insurance companies have been subject to comprehensive standards for the collection, use and disclosure of personal information in connection with insurance transactions. These privacy laws and regulations were developed over decades pursuant to the federal Gramm-Leach Bliley Act (GLBA), and California’s Insurance Information Privacy Act (IIPPA), and the California Financial Information Privacy Act (CFIPA). These three Acts combine to provide significant statutory and regulatory consumer privacy protections that are specifically crafted for oversight of the insurance industry.

Enacted in the wake of highly publicized data privacy scandals involving the technology sector, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) is a sweeping new privacy law that applies to businesses of all sizes in nearly every industry, which hastily passed the legislative process without input from crucial stakeholders. Despite the passage of CCPA, the proponents of the measure moved forward with a ballot initiative in 2020, known as the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) imposing additional liability risks on companies doing business in the state.

The CCPA and CPRA create a convoluted regulatory structure that is enforced by three separate regulators (the Insurance Commissioner, the Attorney General, and the California Privacy Protection Agency). Requiring compliance with differing laws and regulations that are enforced by separate regulators is untenable. This regulatory structure creates substantial compliance costs, confusion, and delay for consumers and insurers. For example, the IIPPA requires insurers to protect the privacy of California consumers, and already covered many of the same aspects as the CCPA including:

- What personal information is protected

- Whose personal information is protected

- Requiring disclosure of a consumer’s rights regarding the collection and use of protected information

- Permits consumers to opt-out of sharing marketing information

- Addresses a consumer’s right to have information deleted or amended

- Requiring insurers to have detailed security programs designed to protect the personal information they hold; and

- Subjects insurers who violate the provisions of the IIPPA to sanctions

PIFC supports exempting insurers, insurance agents, and insurance support institutions from the CPRA and CCPA. The insurance industry is already subject to robust state and federal privacy rules that are substantially similar to the CCPA and CPRA consumer protections, but are specifically designed for the unique challenges of the insurance industry.